The case of Kumar Lama is actually good news for international justice

An Op-Ed by Valérie Paulet

Despite his acquittal, the trial of Colonel Kumar Lama in the United Kingdom goes to proving the relevance of universal jurisdiction.

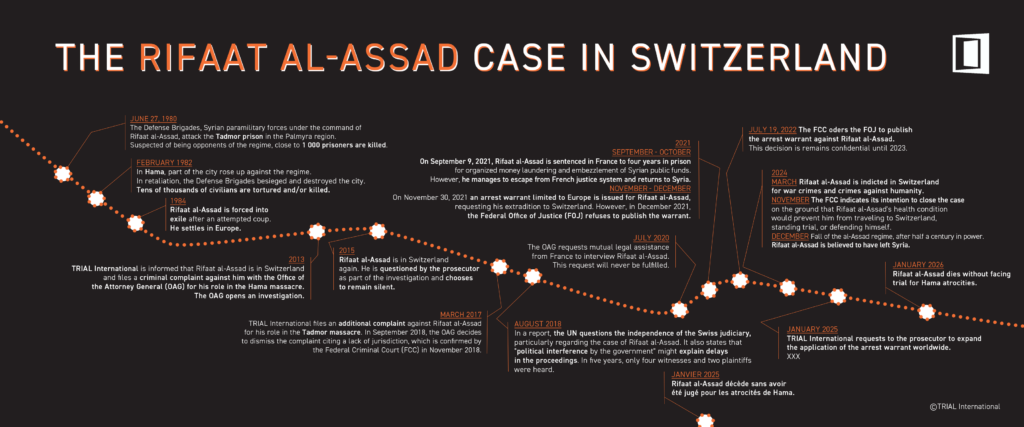

In 1961, Adolf Eichman was arrested in Argentina and subsequently convicted in Jerusalem. To many, this was considered the first universal jurisdiction case: the prosecution of international criminals, wherever the crime took place and regardless of the nationality of the suspects or the victims. This historical milestone was followed by others: the arrest of Augusto Pinochet and the convictions of Pascal Simbikangwa and Hissène Habré, to name but a few.

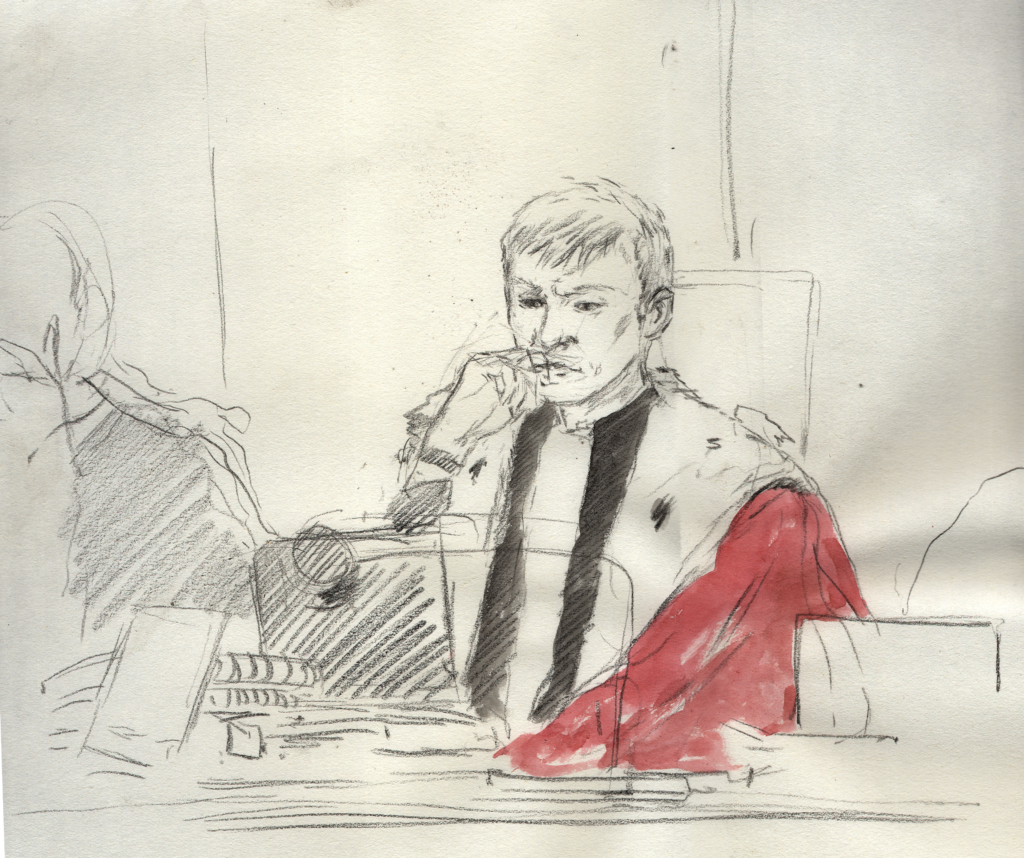

In September 2016, the United Kingdom (UK) closed its second trial on universal jurisdiction cases: that of Colonel Kumar Lama. The Nepalese Colonel was arrested in early 2013 during a personal visit to the United Kingdom. He was indicted for the alleged torture of two detainees during the civil conflict in Nepal.

Mr. Lama’s trial started on 24 February 2015 at London’s Old Bailey. After a rather complicated trial, he was finally acquitted of all charges for lack of evidence.

Does this acquittal represent a step backwards for international justice? Certainly not, for at least three reasons.

The UK walked the talk

Firstly, the case of M. Lama demonstrates how seriously the United Kingdom takes its obligation to investigate and prosecute torture allegations. The Metropolitan police service, with the support of local NGOs, sought evidence with a thoroughness that has so far escaped Nepal.

Sufficient financial means were also allocated to the inquiry, despite criticism from some domestic parties. The case of Faryadi Sarwar Zardad (2005) had already proved the United Kingdom as a strong promoter of universal jurisdiction, ready to invest human and financial resources to bring these cases to justice.

Taking diplomatic risks

Secondly, the UK took a diplomatic risk by arresting M. Lama, which is rare enough to be saluted. Indeed, the Colonel was not only serving in his national army but also in the UN Peacekeeping mission in South Sudan.

All too often, States renounce prosecuting eminent figures to preserve their diplomatic relations. As recently as 2015, Spain dropped its Tibetan genocide case under the pressure of the Chinese government. It even restricted its national legislation to make sure they would not face more political hazards.

France had also followed this path in 2014, allowing the head of the Moroccan secret services to leave the country despite his indictment for torture.

A way to justice

Thirdly, M. Lama’s case showed many victims what universal jurisdiction is: a way to justice. Ten years after the Peace Agreements, Nepal has not opened a single trial for the countless claims of torture lodged before its courts.

This trial sends a strong signal to Nepal and to other countries in post-conflict transition, where justice can be traded off for a hasty (and superficial) national reconciliation. For victims in Colombia, Salvador, Chad and elsewhere, the case of M. Lama proves that there are fewer safe havens for war criminals than ever before – and that is exactly what universal jurisdiction is about.

Valérie Paulet, Trial Watch Coordinator