Enforced disappearances: Mexico ‘well equipped’ to turn the tide if political will is there

Each year, thousands of migrants from Central America disappear in Mexico, adding to the already staggering number of disappeared Mexican nationals. With a new government voted in and a growing international focus on migrations in Latin America, can Mexico effectively tackle this crime?

TRIAL International and the Fundación para la Justicia y el Estado Democrático de Derecho are filing a report to the UN on enforced disappearances in Mexico. In which context does this submission occur?

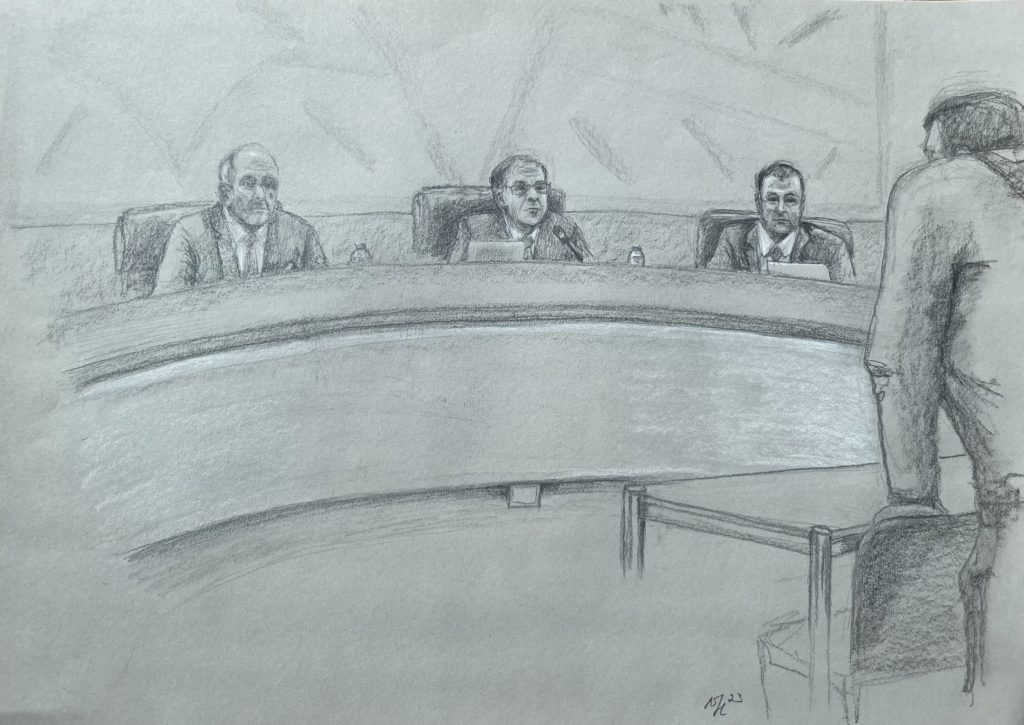

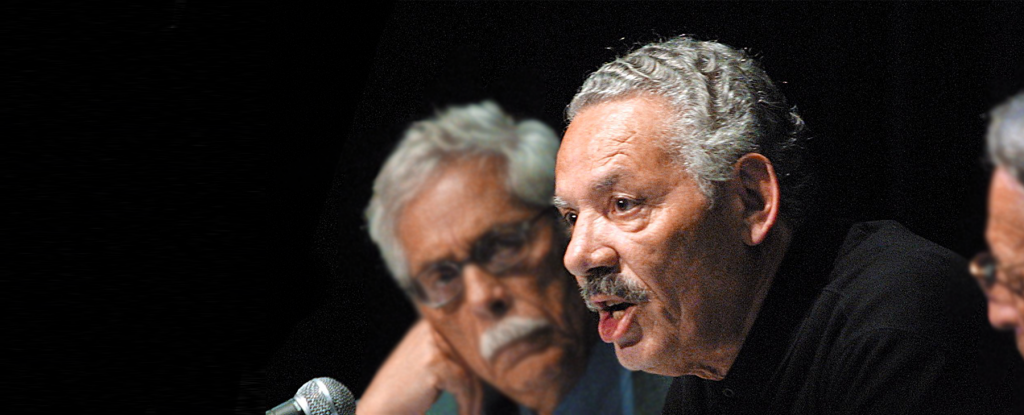

Gabriella Citroni, Senior Legal Advisor at TRIAL International: The UN Committee on Enforced Disappearances (CED) is examining the situation of Mexico for the second time since its creation. The State presents its report to the CED, and civil society organizations may file additional reports to provide an alternative viewpoint. The particularity of our joint report is that it focuses on the enforced disappearance of migrants in Mexico.

How has the situation evolved since Mexico’s last examination in 2015?

Ana Lorena Delgadillo, Executive Director of the Fundación para la Justicia: In the last years, we have witnessed an increase in enforced disappearances, prompting us to assert that Mexico is failing to its international obligations. This is paradoxical, because in 2017 the country passed extremely progressive legislative measures (known as the General Law) to fight enforced disappearances. But these improvements have remained dead letter so far: the victims’ families are still lacking effective mechanisms to search for their love ones, and access to truth and justice.

Can you give examples?

Gabriella Citroni: The General Law could be one of the most comprehensive legal tools on enforced disappearance in the world. Two other measures, created under the advocacy of families and of the Fundación para la Justicia, are particularly progressive. The first was the creation of an interdisciplinary Forensic Commission specifically mandated to identify the mortal remains of the victims of three massacres that took place between 2010 and 2012, many of them migrants. The second was the Transnational Mechanism for access to justice, a provision for families in Central American States to seize Mexican authorities via its embassies and consulates – a crucial point given how difficult it can be for migrants’ families to access Mexican justice.

Ana Lorena Delgadillo: The problem is that some of these improvements remain theoretical. The new National Commission for searching the disappeared – created under the General Law – lacks sufficient financial or human resources. The families of the victims are still doing this work.

Access to justice for families outside the country has also stalled. The Transnational Mechanism for justice has been created but Mexico has no permanent staff dedicated to enforced disappearance in the Central American States the migrants are from (mainly Honduras, Nicaragua, El Salvador and Guatemala). The families’ requests must therefore go through visiting officials, who only come a few times each year. In the meantime, families are suffering daily from uncertainty about their relatives’ fate and whereabouts.

What do you hope the report will change?

Gabriella Citroni: On the positive side, I think there is growing awareness on enforced disappearance in Mexico, especially involving migrants. Another encouraging factor is that Mexico does have the legal arsenal to effectively prevent and eradicate enforced disappearance, and our report gives a very concrete roadmap to put it into practice. So if the political will is there, the authorities are well-equipped to initiate change.

Ana Lorena Delgadillo: There is also a political momentum: Mexico has just voted in a new government. We have met with its representatives and hope that they will take the crime of enforced disappearance seriously. Victims’ relatives are highly organized and incredibly courageous. They have always been at the forefront of the fight against impunity, often taking investigations into their own hands when the authorities failed them. The new government must pay head to the expertise they have developed, respect and improve the good practices such as the Forensic Commission and the Transnational Mechanism for access to justice, and lean on the international community for assistance. Given the scale of impunity in Mexico, only a joint effort has a chance to bring improvements.

Read the full report to the Committee on Enforced Disappearances (in Spanish)

Read the report’s executive summary (in English)

Learn more on enforced disappearances