Irma Leticia Hidalgo Rea v. Mexico

In the night between 10 and 11 January 2011, a group of heavily armed men broke into Ms. Hidalgo Rea’s house, threatened and beat the members of the family and eventually took away her son Roy (then 18 years old). The fate and whereabouts of Roy remain unknown since then and no one has been judged and sanctioned for this crime. Following a complaint submitted by TRIAL International and the Centro Diocesano para los derechos humanos Fray Juan de Larios on behalf of Ms. Hidalgo Rea, the United Nations Human Rights Committee qualified the abduction of Roy Rivera as an enforced disappearance in March 2021. The Committee called on the State of Mexico to investigate his disappearance and provide reparations to his mother.

The Case

In the early hours of 11 January 2011, a group of armed and camouflaged individuals burst into the home of the Hidalgo Rea family in San Nicolás de los Garza, Nuevo León. Some of them wore anti-bullet vests from the Escobedo Municipal Police. At that time, in the house were Ms. Irma Leticia Hidalgo Rea and her two sons Ricardo (who was then 16 years old) and Roy (who was then 18 years old). After having beaten the two brothers and insulted and threatened Ms. Hidalgo Rea, the armed men took Mr. Roy Rivera Hidalgo, whose fate and whereabouts remain unknown since then. In addition, some objects and property, including two vehicles, belonging to the family were stolen.

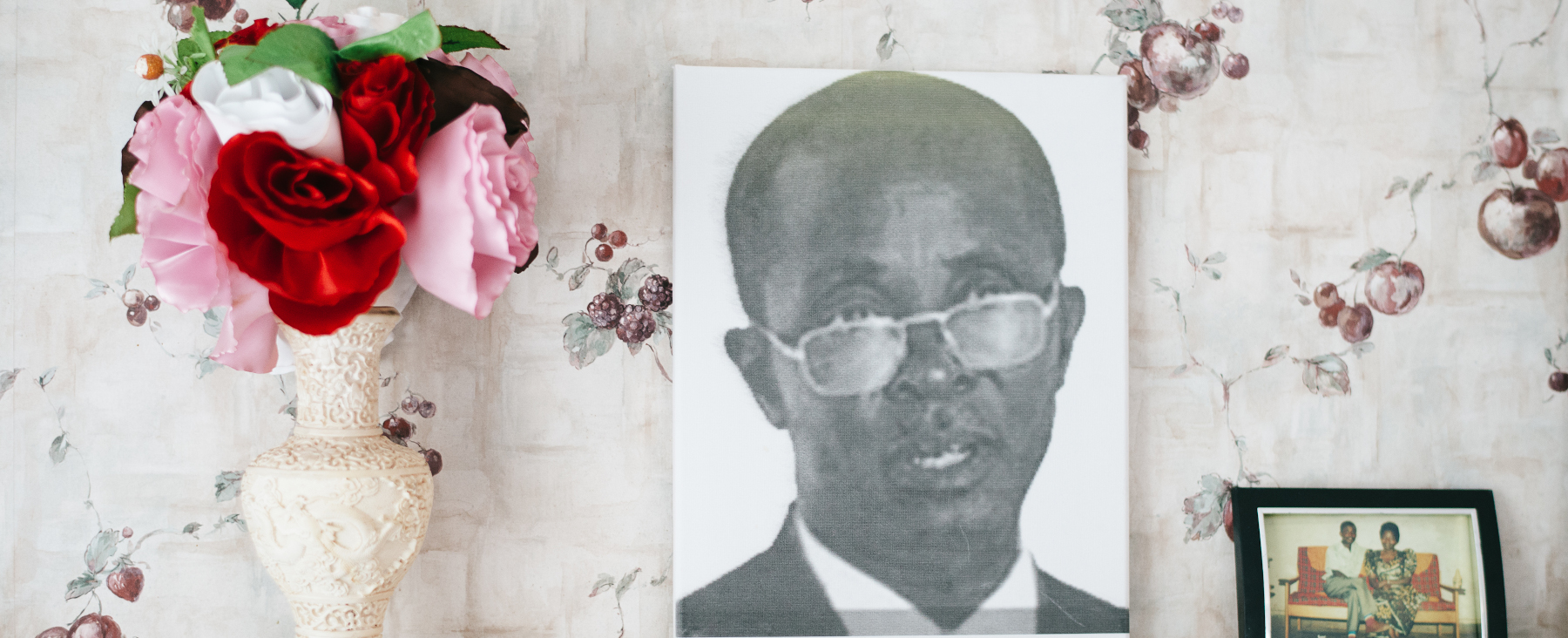

As a consequence of Roy’s enforced disappearance, Ms. Hidalgo Rea and her youngest son Ricardo suffer serious psycho-physical affectations. When her son disappeared, Ms. Hidalgo Rea worked as a teacher. However, since then he has not been able to return to her job, in order to fully dedicate herself to the search of Roy. Currently she is the director of the organization “United Forces for Our Disappeared in Nuevo León”. She has been subjected to constant threats and reprisals.

The Quest for Justice

Ms. Irma Leticia Hidalgo Rea reported the facts before numerous Mexican authorities, including the State Attorney General’s Office, the State anti-kidnapping agency, the State Human Rights Commission of Nuevo León, the Unit specializing in the investigation of crimes against the health of the Sub-Attorney’s Office specializing in investigation against organized crime, and the Search Prosecutor’s Office. This was to no avail: the crime remains unpunished, the fate and whereabouts of Roy have not been elucidated, and Ms. Hidalgo Rea and her youngest son Ricardo have not received compensation or other forms of reparation for the enormous damage suffered.

In January 2018, with the support of TRIAL and the Centro Diocesano para los derechos humanos Fray Juan de Larios, Ms. Hidalgo Rea turned to the United Nations Human Rights Committee (HRC).

In October 2018, the HRC registered the case and transmitted it to Mexico. The authorities have 6 months to submit their reply.

On 25 March 2021, the United Nations’ Human Rights Committee found that Roy Rivera Hidalgo’s abduction from his home in Nuevo León was indeed to be considered an enforced disappearance. The Committee called on the State of Mexico to investigate his disappearance, share information about his fate and provide reparations to his mother

Alleged Violations

In her complaint, Ms. Hidalgo Rea requested the HRC:

- To declare that her son Roy is a victim of a violation of 6, 7, 9 and 16 (right to life, prohibition of torture, right to personal liberty, and right to recognition as a person before the law), read alone and in conjunction with Art. 2, para. 3 (right to an effective remedy), of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights because of his enforced disappearance and the subsequent absence of an exhaustive and effective investigation, both as regards the search of Roy and the identification of those responsible, their prosecution and punishment. The aforementioned provisions are also considered to be violated due to the failure to adopt adequate reparation and compensation measures for the damages suffered.

- To declare that she is a victim of a violation of Art. 7 (right not to be subjected to torture), read alone and in conjunction with Art. 2, para. 3), of the Covenant, because of the ongoing anguish and suffering and the psychological affectations caused by the enforced disappearance of her son and the uncertainty about his fate and whereabouts, as well as the attitude of indifference shown by the Mexican authorities in the face of her.

- To declare that she is also a victim of a violation of 17, para. 1 (right to family life), read alone and in conjunction with Art. 2, para. 3, of the Covenant due to arbitrary and illegal interference in her home and family and the absence of an effective remedy against such interference by the Mexican authorities. These provisions are violated also because of the failure by Mexican authorities to adopt the appropriate measures to guarantee Ms. Hidalgo Rea’s right to know the truth about the fate and whereabouts of her son and to search for him and, in the event of his death, to locate, respect and return his mortal remains.

- To request Mexico to search for and unveil the fate and whereabouts of Mr. Roy Rivera Hidalgo; to investigate, prosecute and sanction those responsible for this crime; and to ensure that Ms. Hidalgo Rea and her youngest son Ricardo receive integral reparation, including restitution, rehabilitation, satisfaction, compensation and guarantees of non-repetition.

In accordance with the Committee’s decision of March 2021, it is now up to the Mexican State to conduct a prompt, effective, thorough, independent, impartial and transparent investigation into the circumstances of Mr. Rivera Hidalgo’s enforced disappearance. The decision also states that Mr. Rivera must be released if alive, or, in the event of his death, his remains must be returned to the family. Finally, those responsible must be prosecuted and sanctioned, the results of the investigation must be communicated to Mr. Rivera’s mother and she must obtain adequate compensation for the harm suffered, as well as medical and psychological assistance. Mexico has 180 days to inform the Committee about the measures adopted to implement the decision.

Context

The enforced disappearance of Mr. Roy Rivera Hidalgo occurred in the context of a situation of widespread disappearances across Mexico’s territory. As of the end of 2017, the government acknowledged more than 34,500 missing persons, many of which have been subjected to enforced disappearance. Almost absolute impunity reigns over these crimes. The authorities’ failure to provide access to justice to victims and to unveil the truth on the fate and whereabouts of disappeared persons results in structural impunity, whose effect is, in turn, to perpetuate and even foster the repetition of grave human rights violations.